Most people will run tests written in Cypress via the built-in test runner. It provides much of the information people need when looking at tests and checking whether it is doing what it is supposed to do – test status, command logs, app preview for each test run, plus snapshots of test steps. Very useful when looking at test failure points.

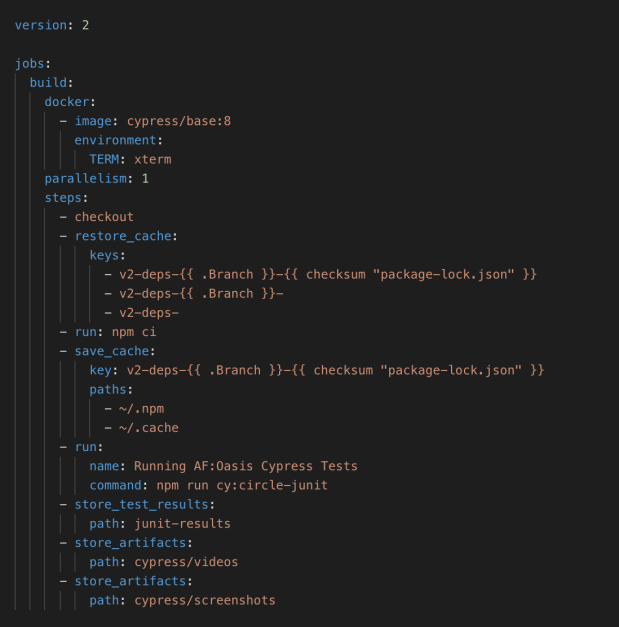

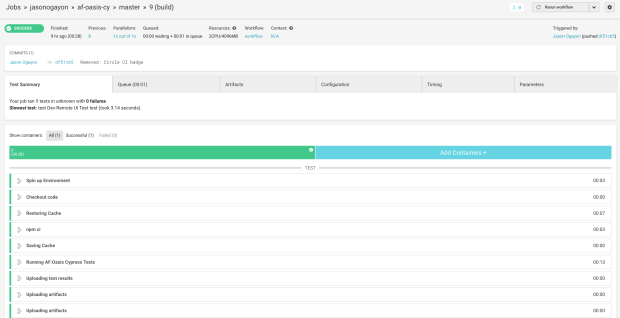

Some people, however, like to run Cypress tests using the terminal or the command-line interface. Sometimes, we don’t necessarily have to see the test running over the app UI. For one, I can start writing a draft of a new set of tests while the existing test suite runs in the background; I will want to know if there are failing tests, but not get distracted by them running on the test runner. That’s how tests run on a CI server too; we just want the test results.

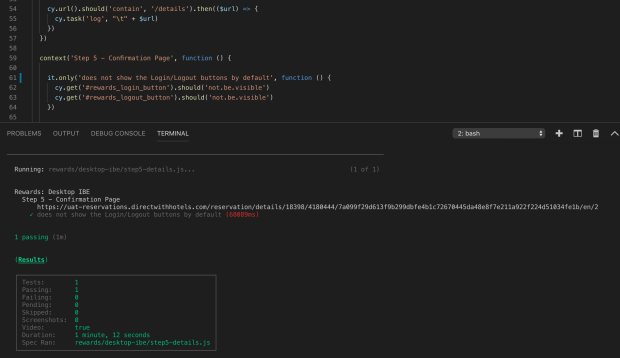

Cypress works well for both scenarios. There’s just less information displayed on the CLI from running tests by default. To help us debug failing tests without opening the test runner, we could print out information we need from the test as it runs. If we want, we can show network request and response pairs, or simple variable values. Often, I find that printing out the URL at certain point for some tests helps me understand test results better. I can also click that URL to redirect me to the page afterwards if there are details I want to check out later for myself.

In order to print that URL to the terminal, we’ll need to add a task to Cypress as a plugin. To do that, we open the plugins/index.js file and add a log task there, like so:

After that, we can now use the log task inside our tests. Here’s an example: